During the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020-2021, I conducted an extensive study with my research colleagues, Helene Castenbrandt and Bárbara Ana Revuelta-Eugercios, on how Danish genealogists use digital platforms to search, save, and share historical information. This was done both in their personal genealogy pursuits and as part of a global network of other history enthusiasts. In this article, I will outline some of our most intriguing findings.

If you are curious about what else is happening within the topic, you can follow the Facebook group: Forskning i slægtsforskning

The article itself, in English, was published in the peer-reviewed academic journal, Archival Science, and is freely available for download:

Roued, Henriette, Helene Castenbrandt, and Bárbara Ana Revuelta-Eugercios. 2023. ‘Search, Save and Share: Family Historians’ Engagement Practices with Digital Platforms’. Archival Science 23 (2): 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-022-09404-4

Questionnaire as a method

In our study, we used a survey to collect quantitative data on Danish genealogists’ use of digital platforms, their experiences with the advantages and challenges online, and their information behavior. The survey was distributed via SurveyXact in November 2020 through popular Danish genealogy groups on Facebook and archive contacts. It resulted in 539 responses, representing a realistic geographical distribution, with a predominance of women aged 65–74. Respondents had experience working (including voluntarily) in fields such as office, IT, health, and care. The results enabled us to identify patterns and further explore the topic through qualitative focus group interviews.

Focus group interview as method

At the beginning of 2021, we conducted six focus group interviews via Zoom with 21 participants (divided into groups of 3-4) recruited from our survey study. Participants were segmented based on which digital platforms they used for genealogy: public, non-profit, commercial, or social media. COVID-19 restrictions made virtual interviews a natural fit for participants, allowing us to gather individuals regardless of geography and easily record the discussions. The interviews focused on the advantages and disadvantages of the platforms and provided valuable qualitative insights into attitudes and emotions, supplementing the survey data and helping to develop our model of genealogists’ engagement with digital platforms.

Genealogy is about the journey, not the destination

To outsiders, it might seem that family history primarily concerns discovering familial connections. Commercial companies often advertise the ability to quickly uncover one’s lineage through simple searches or automated systems. Simultaneously, television programs present family history as a service delivered by professional historians, archivists, or hosts who appear at one’s doorstep. This creates a misleading image of family history as a passive process where a completed family tree is simply handed over. It might also suggest that those providing sources online, whether commercial or not, should focus on reducing the genealogist’s workload.

Participants in our focus group interviews were asked about their views on a platform that allows one to quickly find their lineage with little effort. One participant concluded: “family history would probably also get a bit boring if you could just go in and voilà, there it was”.

In another interview, a participant said:

It’s all about using your imagination… What’s exciting about family history is that it’s kind of like detective work, you dig and then you find something. And it’s really great when you find something. And it can take a long time, and you have to take detours and then you end up on the wrong track. Then we just start over. That’s what I find exciting and without that, it’s not really family history at al.

Another participant responded:

As someone fairly new to family history, I agree with you. The fun part is what you find yourself, not what others have found for you.

This understanding is also evident from earlier studies of family historians, such as those conducted by Fulton in 20091 and Bottero in 20152. They show that the detective work involved in uncovering the family’s history is often central, and not just knowing the family’s history. When family historians talk about what they have discovered, a large part of the narrative also concerns their own experiences in finding the history.

This is further confirmed by the fact that Danish family historians do not use single platforms, but rather a broader array of different platforms. And this itself is not a problem, but rather a fundamental condition in family history that fits well with the practice and detective-like behavior we observe.

A buffet of different platforms

“I first see if I can pinpoint where to look in church records and censuses, but otherwise, I try pretty much all of them… all the places I can think of.

This was a statement made by one of the participants in our focus group.

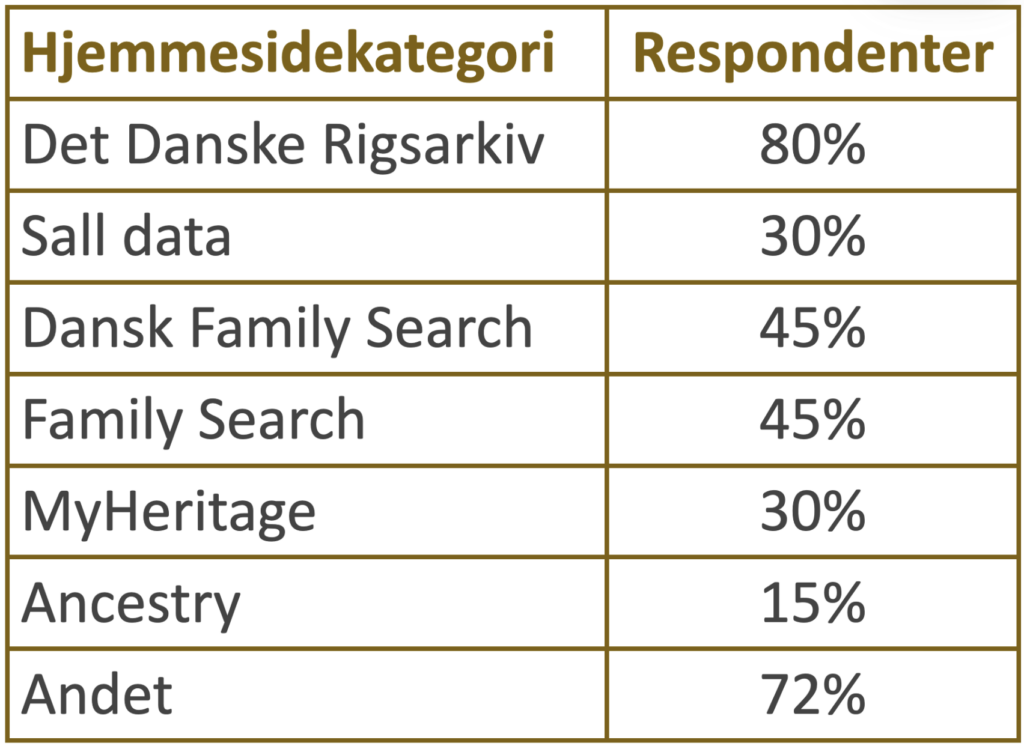

The study revealed a wide and varied use of websites by Danish family historians in their research. A majority of respondents (80% and 72% respectively) used one or more websites offered by the National Archives or as categorized in the “Other” category, as shown in the infobox below. The figures for the most frequently used individual websites are somewhat lower than that. Therefore, we concluded that Danish family historians typically utilise a buffet of websites.

Websites

In the survey, we inquired about the websites most commonly used for family history. Participants could list up to ten websites they used. Subsequently, we categorized the free-text responses into 7 categories. Five of the categories cover individual platforms (Danish Family Search, Family Search, Sall data, MyHeritage, Ancestry). The “National Archives” category encompasses all the different platforms offered by the National Archives (e.g., Arkivalieronline, Dansk Demografisk Database, Daisy, etc.). The last category, “Other,” is the broadest category and covers more than 100 different websites created by associations, archives, and private entities both in and outside Denmark (e.g., Danske Slægtsforskere, Københavns Stadsarkiv, Mediestream, or lægdsruller.dk).

A pattern emerges

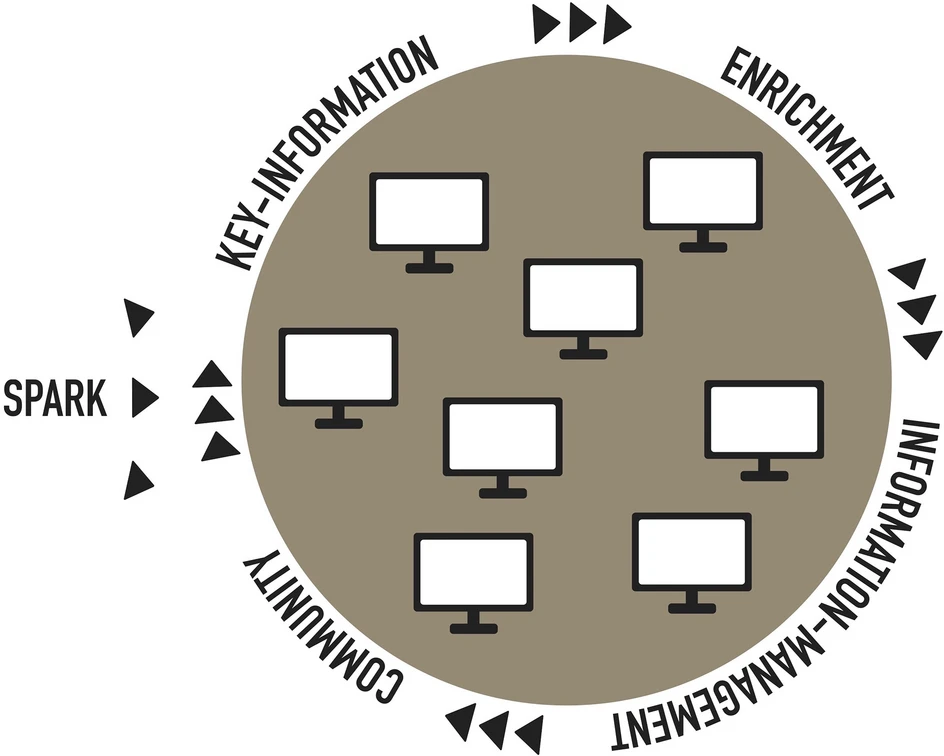

Our study confirmed understandings from earlier research such as those conducted by Duff and Johnson in 20033 and Friday in 20144 which characterize family history as a lifelong activity with a cyclical practice. Within this practice, we have been able to identify several phases in which interactions with various websites occur.

Initially, there is a “spark.” This may be a significant or minor event that initiates a genealogist’s interaction with one or more websites. It could be a tragic event, such as the loss of an elderly family member. For me, as for many others, it was the task of sorting through the photos and documents my grandparents left behind that ignited my interest in family history 20 years ago.

A spark can also be a joyous family event, such as when an experienced genealogist shared how they started researching a new branch of the family tree following the birth of a grandchild. A spark might be a TV program, an advertisement, or a post on social media.

A spark could be encountering a new source, method, or website that launches a new round of genealogical research. Having been a genealogist through two decades of ongoing digitization and transcription of sources, one experiences the increasing availability of more and more sources. Over half of the family historians we heard from, like myself, have been conducting family history since the 2000s when this digitisation intensified.

Finally, a spark can be having the time for family history. Many associate it with older people who start when they retire. It is true that family history requires time. It can be challenging to find space for it in a busy life with young children and full-time work. Nonetheless, only a quarter of the family historians responded that they conducted more family history when they were not working (i.e., retired, students, or unemployed). Although half of the participants were retirees, their extensive experience showed that few of them had started only after retirement.

Family historians’ use of the internet

When a spark initiates a round of genealogical research, family historians employ a buffet of websites and platforms to find information, organize it, and share it with others.

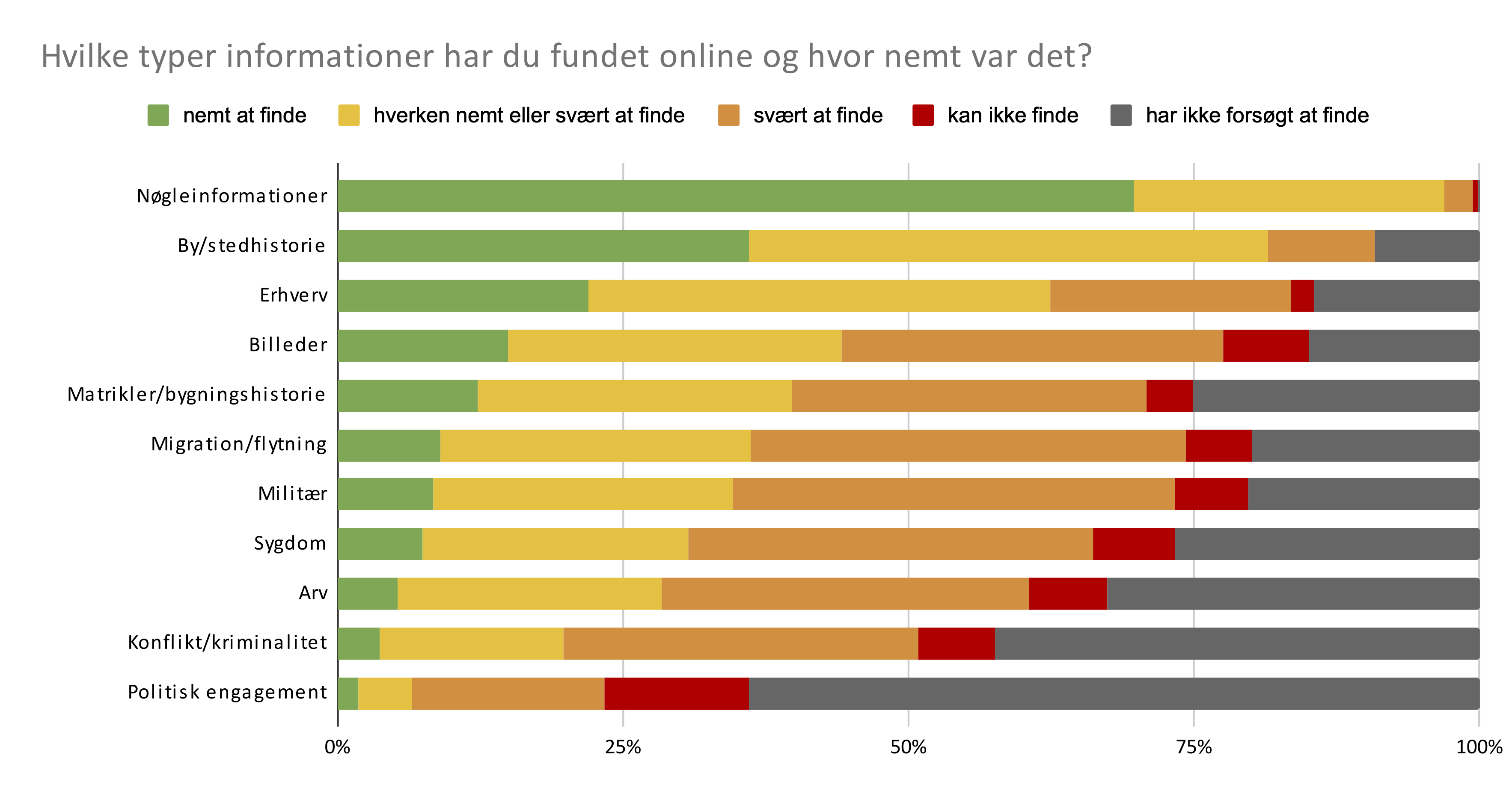

We have divided the information search into two phases. The first concerns finding key information. The second involves enriching this with more in-depth stories.

Key information typically includes details such as births, marriages, deaths, and familial relationships—essentially, the data used to populate a family tree. Only a very small percentage of family historians in the study felt that this information was difficult to find. Such information is usually located in the many church records and censuses that family historians have helped make available online since the 1990s.

This stands in stark contrast to other types of information we inquired about—information that can enrich the family tree with narratives about family life and experiences. Here, family historians more often felt that such information was hard to find, that they could not find it, or that they had not even attempted to. Experience also plays a role. The more experience one gains in family history, the more one explores the diverse stories about professions, migration, or political engagement.

This may be due to the difficulty of accessing such information and its lesser availability online. Since recruitment for the study primarily took place online, it is unsurprising that virtually all used the internet for their genealogical research. Therefore, we cannot comment on the extent to which family history without the use of the internet still occurs, or how it is conducted today. Almost everyone highlighted the greatest advantage of using websites as being able to decide where and when to delve into family history, followed by the ability to access information from home. However, nearly a third found it a disadvantage that not everything was available online. As one participant in the focus groups said:

For me, the online platform was an important gateway to getting started. When you are working, the idea of running around looking at church records and visiting libraries and so on is definitely a barrier. So having the ability to come in and search across various sources was really what got me started.

Family historians also use the internet to organize and store the information they find about their lineage. This is just as important a part of the genealogical practice as finding the information in the first place. Especially when one has been conducting family history for two decades and cannot always remember which information has been found or which sources have already been searched, I must say. Today, we are accustomed to not needing to store the information we need for daily use ourselves. The knowledge we find today can also be searched for and found tomorrow, perhaps in a more updated version. But it is precisely the essence of family history, not just to find information, but to actively use it and integrate it into the story one is creating about the lineage.

Almost all family historians stored the information in some way. However, there was considerable variation in methods, and multiple methods are often used simultaneously. Just over half used an app or a program on their own computer, and slightly over a third used a word processing program. Perhaps surprisingly, a third also used notebooks and loose notes to store their information. The latter was more prevalent among women and younger family historians.

When it comes to this information, there was also a widespread understanding of the importance of critically engaging with sources and information, which are often checked and double-checked. There has previously been a stereotype of family historians as somewhat uncritically trying to find familial connections to historical figures or power holders. However, current research shows that the typical genealogist now has a greater focus on the nuanced and diverse stories that can be found when delving into the lives of ordinary people.

A community

When discussing the modern family historian who prefers to access information from home, it might sound somewhat asocial. This perception is especially stark if one recalls the cozy queues, complete with coffee and pastries, outside regional archives on a Saturday morning 20 years ago, where securing a reading spot required a long journey.

Even at home behind the screen, family historians are rarely completely alone. On one hand, they are part of a community with their own family, which includes both the relatives they research and the living family members who sometimes serve as a somewhat reluctant audience. On the other hand, they are part of a larger community of other family historians with whom they interact through social media. For the fortunate, these communities merge into one when, as I have experienced, a family member becomes as enthralled with family history as oneself.

Many family historians utilize social media in their genealogical research. Many use social media to keep up with the community and receive news. However, very few use it to share their own stories. The primary use of social media for family history is to seek assistance with reading handwriting and finding information. The theme of receiving help from other family historians on social media was also prevalent in our focus group interviews.

Fortunately, there are some, a bit older but good experienced family historians who can help us who can’t figure it out. That’s what I think is great about these groups on Facebook […] then it doesn’t take more than 20 seconds before someone has answered.

And it’s all day long. It’s absolutely fantastic, such dedicated people sitting behind that group. I really think that’s amazing.

Facebook group: Slægtsforskning

The Facebook group primarily referred to is one that was created in 2007 and is administered by the association Danske Slægtsforskere (Danish Genealogists). The group Slægtsforskning (Family History) is the largest Danish Facebook group on the topic, and when we conducted the survey in 2022, it had around 25,000 members. By the end of 2024, this number had increased to 34,000 members

It’s not just about receiving help that’s important. Participants also talk about giving help and generally creating an environment where people assist each other. As an important aspect of an environment where the focus is on improving collectively and creating a shared practice: As one said:

Well, if people ask something, they should get an answer, if you can help. I think that’s quite straightforward. It doesn’t cost anything.

Another replied:

Well, we all sit with the same problem, so if it’s not me today, it’ll be someone else tomorrow. And if I got help yesterday, then I might as well help. I’ve also helped people in these family history groups. So what you receive, you can also give back.

At the same time, every post creates a new thread of information and knowledge that can be retrieved in the future. It is not so rare that I search for something about my own lineage, only to find a thread I may have started 15 years ago, to which others have since added what they knew about the topic. This speaks to an understanding of family historians as both family historians and family archivists, both individually and collectively. Family history practice as a cultural heritage activity is not about “getting” one’s family history. It’s about finding it. It’s about assembling and remembering it, while also sharing the family’s history and creating genealogical practice with others.

If you wish to read the original research article, a link to the freely available version is provided above (link to the top).

- Fulton, Crystal. 2009. ‘The Pleasure Principle: The Power of Positive Affect in Information Seeking’. Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives 61 (3): 245–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530910959808. ↩︎

- Bottero, Wendy. 2015. ‘Practising Family History: “Identity” as a Category of Social Practice’. The British Journal of Sociology 66 (3): 534–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12133. ↩︎

- Duff, Wendy M. and Catherine A. Johnson. 2003. ‘Where Is the List with All the Names? Information-Seeking Behavior of Genealogists’. The American Archivist 66 (1): 79–95. https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.66.1.l375uj047224737n. ↩︎

- Friday, Kate. 2014. ‘Learning from E-Family History: A Model of Online Family Historian Research Behaviour’. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal 19 (4). http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-4/paper641.html. ↩︎